Learning Objectives

- Recognize how melanoma manifests clinically

- Determine differential diagnoses

- Identify management and referral considerations

- Understand proposed pathophysiology

Medical Case 1

A 55-year-old patient from New Zealand presents with a one-year history of a progressively darkening mole on the R lateral calf. The patient is unsure whether there’s been a mole there since childhood.

Social history is significant for 15-pack-per-year smoking and has a history of tanning bed use. Family history is significant only for melanoma in-situ in the patient’s mother at age 84. No constitutional symptoms are endorsed.

On exam, there is a 2×4 cm heterogeneously brown, tan, and black asymmetric patch with irregular borders on the L lateral calf. There is no regional lymphadenopathy.

Medical Case 2

A 38-year-old patient is referred to your office for a history of “many irregular changing moles.” Four biopsies have been completed to date showing dysplastic nevi.

Notably, the patient’s family history is significant for melanoma occurring in the patient’s father and his father’s brother. The same uncle was also recently diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

The patient was born in Canada and social risk factors are unremarkable. On physical examination there is a 1×1.5 cm brown and black asymmetric patch with irregular borders.

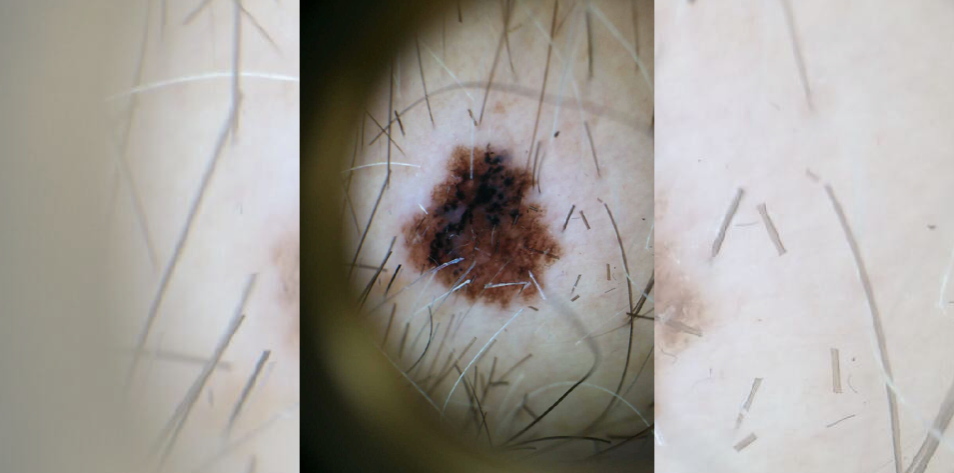

What are the clinical (morphologic) features of concern in both lesions? What concerning dermoscopic features are present in the latter?

Both cases demonstrate morphologic asymmetry with border irregularity, color variegation and a size >5mm, as well as a history of evolution. The former case displays the gross morphological features of melanoma, which can also be appreciated in the latter dermatoscopic image (using polarized light magnification).

Stratifying a patient’s risk of melanoma improves pre-test probability in the evaluation of a lesion and decision to proceed with a biopsy, which may result in scarring and heightened patient anxiety. A thorough history including exposure risk factors such as Fitzpatrick phototype (always burn [I] vs. sometimes burn, mostly tan [III]) artificial tanning, endemic UV, sunscreen use, smoking, immunosuppression, and family history of cancers. Notably, familial atypical multiple mole melanoma (FAMMM) syndromes caused by mutations in the tumor suppressor gene CDK2A (p16/p14-ARF) also carry a considerably high burden of pancreatic cancer (20%), in addition to melanoma. A clinical diagnosis is made based on the presence of >50 atypical nevi, a history of severely dysplastic nevi and/or a history of melanoma in one or more first- or second-degree relatives.

In patients presenting with numerous epithelioid or spitz-type atypical nevi and familial history of uveal melanoma. A prudent history would include family history of lung (mesothelioma) and/or renal cancers as part of screening for potential BAP1 melanoma syndrome. Clinically, these melanomas often present with little-to-no pigment and are characteristically identified by evolution alone.

When evaluating a pigmented lesion by dermoscopy, there are several algorithms to improve diagnostic accuracy. The seven-point checklist describes seven criteria in major (two points each) and minor (one point each) categories, with a total score of >3 suggesting biopsy. Major criteria include presence of a blue-white veil, irregular vascular pattern and/or atypical pigment network; minor criteria consist of streaks/streaming/pseudopods, irregular dots and globules, regression, and irregular blotches.

Patient education is of critical importance for self-surveillance and discussion of the clinical ABCDEs of melanoma (asymmetry, border, color, diameter, evolution) should be discussed with all patients. In high-risk patients (previous melanoma), family history or syndromic, three- to six-month physician surveillance is recommended.

Further Reading

References

Figure 1 – The future of medical education [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 18]. Figure 1 – The future of medical education. Available from: https://app.figure1.com

Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, Pasquini P, Abeni D, Boyle P, Melchi CF. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: I. Common and atypical naevi. Eur J Cancer. 2005 Jan;41(1):28-44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.10.015. PMID: 15617989.

Goldstein AM, Chan M, Harland M, et al. Features associated with germline CDKN2A mutations: a GenoMEL study of melanoma-prone families from three continents. J Med Genet 2007;44:99–106.

Kittler H, Guitera P, Riedl E, et al. Identification of clinically featureless incipient melanoma using sequential dermoscopy imaging. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:1113–19.

Liu W, Hill D, Gibbs AF, et al. What features do patients notice that help to distinguish between benign pigmented lesions and melanomas?: the ABCD(E) rule versus the seven-point checklist. Melanoma Res 2005;15:549–54.106.

Soura, E., Eliades, P. J., Shannon, K., Stratigos, A. J., & Tsao, H. (2016).Hereditary melanoma: Update on syndromes and management. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 74(3), 395–407. doi.org

Published March 20, 2024

By David Croitoru, MD

Dermatologist

Want more clinical cases?

Join Figure 1 for free and start securely collaborating with other verified healthcare professionals on more than 100,000 real-world medical cases just like this one.