A person’s health is determined by so much more than clinical care. The color of their skin and that of their physician’s, their ZIP code, the water from their tap, their elected officials, the balance of their bank account—the list of social determinants of health goes on.

Physicians and activists are speaking out online about these inequalities. Here are a few examples.

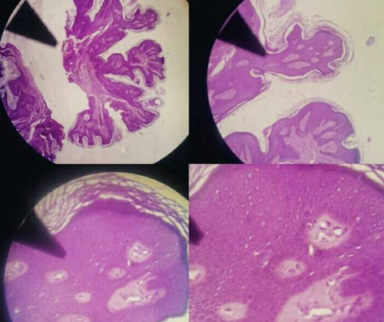

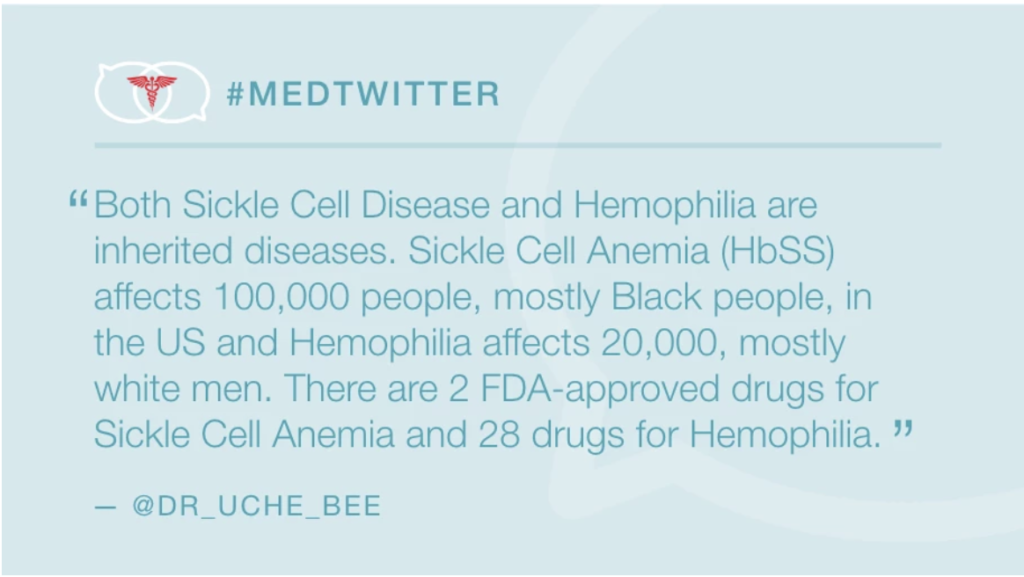

Why Treatments Available for Sickle Cell Disease is Starkly Different From Similar Diseases

Dr. Uché Blackstock, an emergency physician from Brooklyn and associate professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine at NYU School of Medicine, noted that structural racism prevents many black patients from receiving the care they need. Hemophilia is estimated to affect about 20,000 Americans, and currently has 28 FDA-approved drugs for treatment. In contrast, sickle cell disease, affects 100,000 Americans, five times more patients, but can be treated with only two FDA-approved drugs. Although both are inherited diseases, one mainly affects white men while the other primarily affects African-American people.

“The people giving care in America don’t look like America.”

The people giving care in America don’t look like the people who are receiving care American, describes @choo_ek of @TIMESUPHC at #AtlanticPulse, which has proven to endanger patients of color and women. pic.twitter.com/oTyX86lG0H

— AtlanticLIVE (@AtlanticLIVE) April 30, 2019

During a talk at The Atlantic’s Pulse: Summit on Health Care, Dr. Esther Choo, an emergency physician from Portland and founding member of TIME’S UP Healthcare, called the disparity between the people giving and leading healthcare and those receiving it “one very glaringly obvious opportunity for improvement.”

Dr. Choo quoted a study that randomized a group of black male patients from Oakland, California with black and non-black physicians. Those patients randomized to a black physician were much more likely to receive the flu vaccine and other primary-preventive measures such as screening for elevated BMI, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and hypertension.

The study estimated that if this practice were applied across the U.S., the gap in black-white male cardiovascular mortality would decrease by 19%.

“We know lead isn’t just a problem in Flint. We know racism isn’t just a problem in Flint. We know social injustice isn’t just a problem in Flint.”

From @MonaHannaA “The strongest medicine I can prescribe for my kids is a living wage for their parents.” Who knew that understanding economics would be so important to being able to care for our patients and improve the lives of our children. #PAS2019

— Nancy Graff (@NancyGraffMD) April 27, 2019

Flint, Michigan-based pediatrician Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha had seen complaints of rashes and eye irritations from local Flint residents as early as April 2014. It was around the same time that the city’s water supply was switched over from the Detroit River to the less-costly, but much-dirtier, Flint River. After dinner with a friend, who happened to be a former Environmental Protection Agency water engineer, she was determined to conduct a study on the blood lead levels of patients in her clinic. What she found not only confirmed the concerns voiced by the community but exposed a “crime committed with indifference,” as Dr. Hanna-Attisha said at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting in Baltimore this week.

“High prices don’t just mean big medical bills. They also make Americans wary of using our health system.”

Here’s what the mom does:

She drives to the ER. But she doesn’t go inside.

Instead, she and her toddler sit in the parking lot for hours. They watch the Little Mermaid on loop.

The mom thinks: I can go inside if she has a seizure. Otherwise, I can’t afford it.

— Sarah Kliff (@sarahkliff)

Sarah Kliff, a senior policy correspondent at Vox who is investigating emergency care billing, shared a story of a mother and her 2-year-old daughter. The toddler ingested a pill, and after consulting with poison control, the mother drove her to the emergency department. But rather than go in, they sat in the parking lot watching The Little Mermaid for hours as the mother waited to see if her daughter’s condition would deteriorate. The mother thought to herself: “I can go inside if she has a seizure. Otherwise, I can’t afford it.”

White, Working-Class Americans are Voting for Right-Wing Policies That Hurt Marginalized Populations—as well as Their Own Health

My book, https://t.co/eWJmK7YtyQ, shows how Trump/GOP policies that claim to make white America “great again” end up making the lives of working-class white supporters harder, sicker and shorter—and in the end, threaten everyone’s well-being.

— Jonathan M. Metzl (@JonathanMetzl) April 6, 2019

When psychiatrist Dr. Jonathan Metzl launched his book, Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment is Killing America’s Heartland, a group of white nationalists stormed his reading in a D.C. bookstore. In the book, Metzl writes that white, working-class Americans in the South and Midwest are supporting policies that hurt the health of all Americans—including themselves. For the first time in a century, white men are seeing their life expectancy shortened by three years, he said in a NowThis interview.

Today, life expectancy is shortened by funding cuts to healthcare programs that help treat addiction, mental health, and chronic illnesses. Bans on federally funded gun research and, of course, lack of gun control have led to astronomical numbers of suicides, homicides, and accidental shootings. While the health of all Americans suffers when these damaging policies are put in place, Metzl points out that working-class conservatives are choosing the very leaders and policies that are killing them.

Published April 2019, updated February 2, 2022

Join the Conversation

Register for Figure 1 and be part of a global community of healthcare professionals gaining medical knowledge, securely sharing real patient cases, and improving outcomes.